There is a lot of talk about whether we are in a bubble right now. Indexes are right around all-time highs, and it’s no secret they got there on the back of AI hype. The incessant rise in AI stocks has led many to question valuations:

A recent BOA survey found that a record 60% of surveyed investors now say global equities are overvalued, and 54% believe AI-related assets are in bubble territory.

This summer, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, said,” Are we in a phase where investors as a whole are overexcited about AI? My opinion is yes.”

A bubble may not have a strict definition. However, it is generally characterized by asset values rising significantly beyond what is considered justifiable via economics or profits. The problem for fundamental investors is that irrationality has no expiration date.

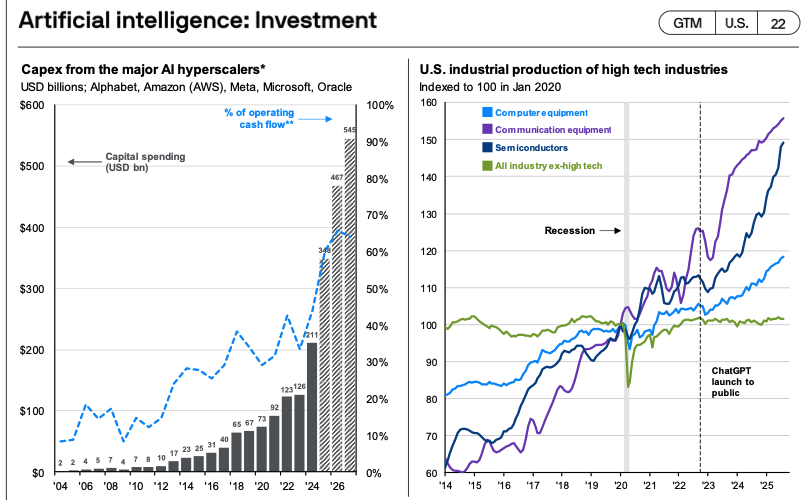

There are some valid concerns. One, the once asset-light profit-growing tech companies are transitioning into more capital-intensive ventures—using large sums of debt and circular vendor financing arrangements. Two, everything tangentially related to data-center construction is experiencing a boom, while the rest of the world gets left behind.

The Magnificent Seven’s Transformation

Big tech’s buildout is the new oil boom

A big part of the reason investors would pay a premium for the tech giants is that they used little debt and very little capital (factories and buildings), while still delivering outsized profits amid astronomical growth. Now, that isn’t the case anymore, causing investors to wonder if the premium is still worth it—paying more and more for less.

Overspending Isn’t New

Wu, the founder and chief investment officer of Sparkline Capital, examined primary capital expenditure cycles throughout history, including:

- Railroad expansion in the 1860s-1890s

- Telecom fiber optic buildout in the late 1990s

- Current AI infrastructure spending (2023-present)

The study specifically tracked how Apple AAPL, Microsoft MSFT, Amazon.com AMZN, Meta Platforms META, Google GOOGL, Nvidia NVDA, and Tesla TSLA are transitioning from asset-light business models to capital-intensive operations.

It examines:

- Historical capital expenditure trends

- Changes in return on invested capital

- Free cash flow deterioration

- Rising debt levels and circular financing arrangements

In his analysis, Wu compared the scale of these investments relative to the gross domestic product (GDP) and investigated how shareholders in infrastructure-building companies fared during and after each period of intense spending.

His work suggests a historical pattern where massive infrastructure spending, while transformative for the economy in the long term, often leads to periods of overcapacity and can be problematic for investors in the short term. His research is available on the Sparkline Capital website.

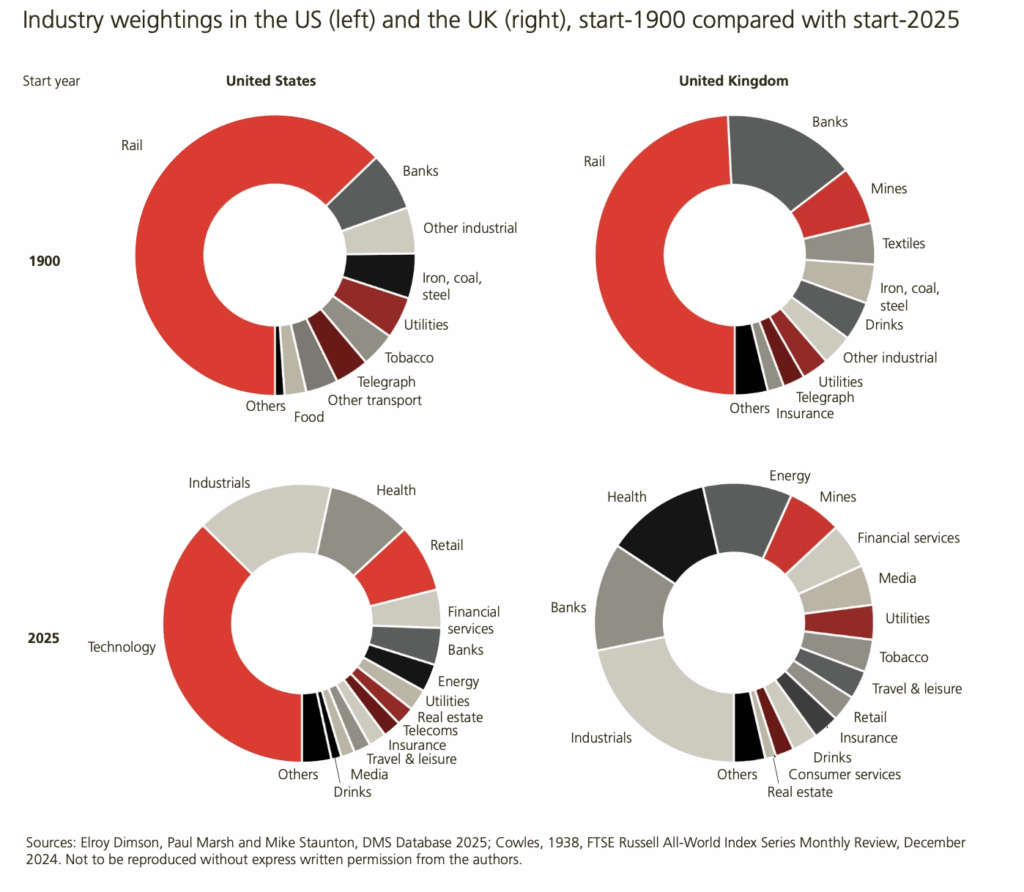

We can see a similar story in equity market valuations during these selected periods of massive capital expenditure. At the beginning of the 20th century, the stock market was 63% railroads.

Circular Vendor Financing

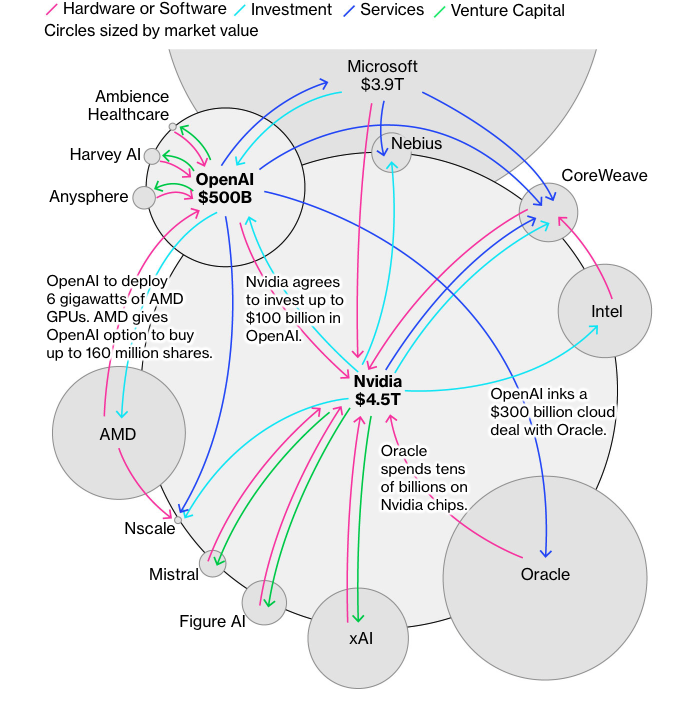

Below is an image from Bloomberg that shows the size and flows of capital to and from AI companies.

If you think it looks like a handful of companies are sending each other the same dollars back and forth, you are correct. It is what it looks like. NVIDIA invests in OpenAI, and then OpenAI uses that investment to buy chips from NVIDIA. Copy-paste similar transactions among a few AI firms, and you end up with this web of flows pushing valuations ever higher.

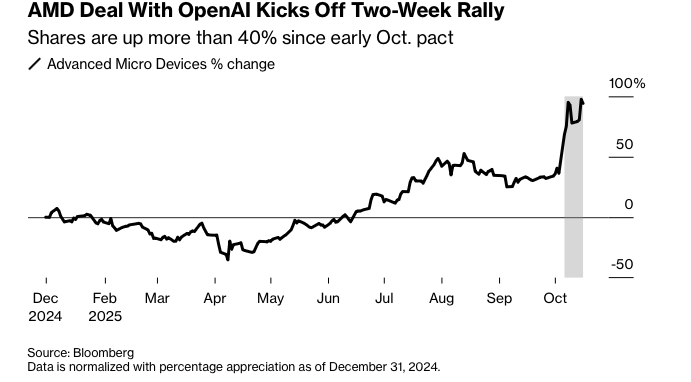

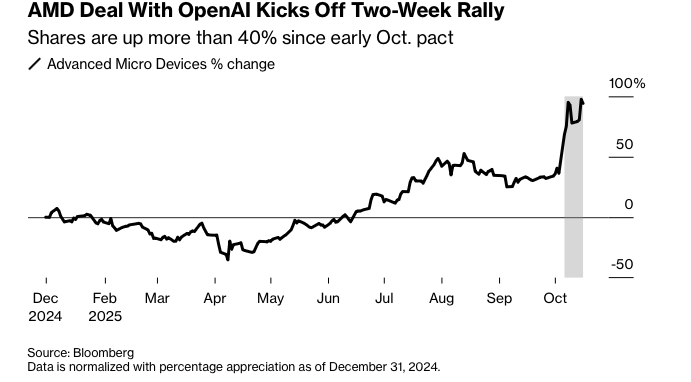

If OpenAI announces a deal with another firm, its valuation skyrockets above the deal’s value—it is wild.

If it seems like a lot…

Eventually, this technology will need to demonstrate real end-user demand to justify its valuation. The value of OpenAI surges to $500 billion, based on approximately $12 billion in annual revenue, but it has made $1.4 trillion in obligations by 2030. Altman got a little testy on this podcast when pressed about all of their capital commitments. It will have to find a better way to make revenue than subscriptions, ads, AI girlfriends, and whatever the hell Sora is.

A recent issue of The Economist noted: For companies to achieve a 10% return on the AI capex projected for 2030, they will collectively need $650bn in annual AI revenues—equivalent to over $400 per year from every iPhone user, reckons JPMorgan Chase, a bank. History shows that such lofty expectations are often disappointed at first by new technologies, even if they go on to change the world.

Translation: Yeah, they are spending a lot of money to build this stuff that has no clear immediate payout for investors, but will eventually be useful. The overbuilding of tech infrastructure in the late nineties gave us today’s apps—it takes a long time.

Not Only Tech Companies

It’s not just the tech companies booming on AI, either. Electrical engineering firms, such as Eaton, and construction equipment firms, such as Caterpillar, are benefiting from surging demand for data center construction.

The tech bros seem pretty content spending wild sums on AI researchers and infrastructure. They are more worried about being first on an AI breakthrough than making money (Zuckerberg already won the money game). If your company is already worth $1.85 trillion, you can pay an AI researcher $100 million without batting an eye.

If Mark Zuckerberg has recently paid you $100 million to join Meta, please set up your Zoom call here.

Speaking of Valuations: Is This a DotCom All Over Again?

Source: JPMorgan

There are some similarities between now and the dotcom bubble (the second-worst bubble of that era). During the DotCom mania, Allen Greenspan made his famous “irrational exuberance” remarks about the market. Nobody ever knows if we are in a bubble before it bursts. It was perhaps Greenspan who demonstrated this the best:

- The S&P 500 stood at 749 in December 1996 when Greenspan made his “irrational exuberance” speech

- When the dotcom bubble burst, the S&P 500 bottomed out at 776 in 2002

- The S&P fell to 676 in March 2009, but that was part of the Global Financial Crisis

Investors may have been overly optimistic with all things related to the Internet, but it is impossible to say at what point that was during the dotcom mania. Can you imagine being an investment manager and pulling all your money out based on Greenspan’s speech, then waiting to get back in at the bottom? You’d be out of a job.

Even if there is a consensus that people are overbuilding and spending too much on this stuff, it is still impossible to know beforehand at which point it is too much. That’s why we only ever know we were in a bubble after it bursts.

It is hard to pick the winners and losers

Tracy Alloway of Bloomberg points out in her recent review of The Internet Bubble: Inside the Overvalued World of High-Tech Stocks, written in 1999, that it is also very hard for the well-informed to pick out the winners and losers of the hype cycle:

Yahoo — profitable, conservatively financed, founder-owned — with Amazon, which was still unprofitable and leaning on junk-bond financing. In 1999, the implication was clear: Yahoo looked like the sturdier franchise, and Amazon looked like the riskier bet. But history flipped that script entirely. Yahoo faded into corporate obscurity while Amazon became a retail and cloud-computing titan — and now sits at the heart of today’s AI boom. The point isn’t that the authors were wrong, but that even well-informed observers can’t reliably pick winners during a frenzy. Mania makes every company look like it’s riding the same wave, when in reality only a few end up catching it.

And if the Yahoo/Amazon anecdote teaches us anything, it’s that bubbles make everyone look like a genius… right up until they don’t. As shown by the Greenspan anecdote above, fundamental valuations and sentiment (vibes for those under 35) can diverge for years before any sort of reckoning. And when it comes, you may still be better off than when the bubble started building. Why bother trying to guess at it?

What You Can Do

Do Nothing

Doing nothing is also an option, and perhaps the best. If you are diversified and thinking in decades, a bubble burst won’t mean much to you. As investing becomes ingrained in pop culture and a social-media sport gambling, ignoring the daily swings gets harder—and yet staying disciplined is still best for long-term success.

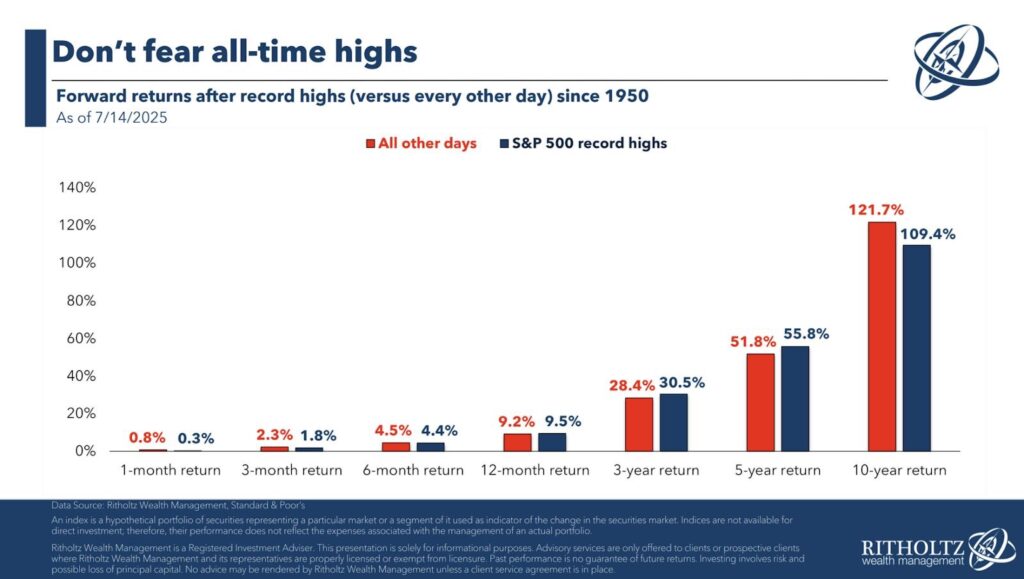

Still worried? Even if you manage to pick the worst time to get into the market, at its peak, you still do pretty darn well over the long run. Being properly diversified and disciplined means you can do nothing and will experience positive outcomes over the long run. Ritholtz has an excellent, albeit incomplete, graphic demonstrating this (I prefer broader indexes).

Diversify

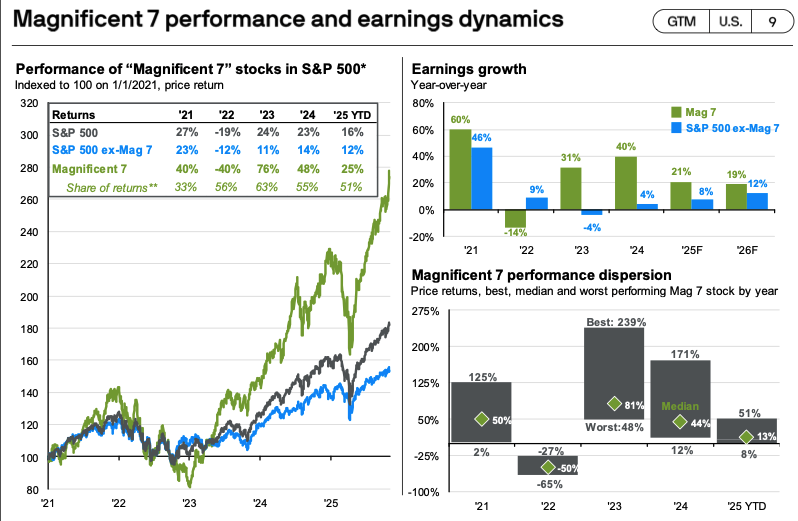

You also need to be diversified. Lame, I know. The S&P 500 has become a giant tech stock, and the broader US market is largely driven by anything tangentially related to building AI infrastructure. I have whined about this for a while hereand here. However, it’s true: market capitalization-weighted indexes are subject to sector and theme concentration, no matter how many stocks they hold.

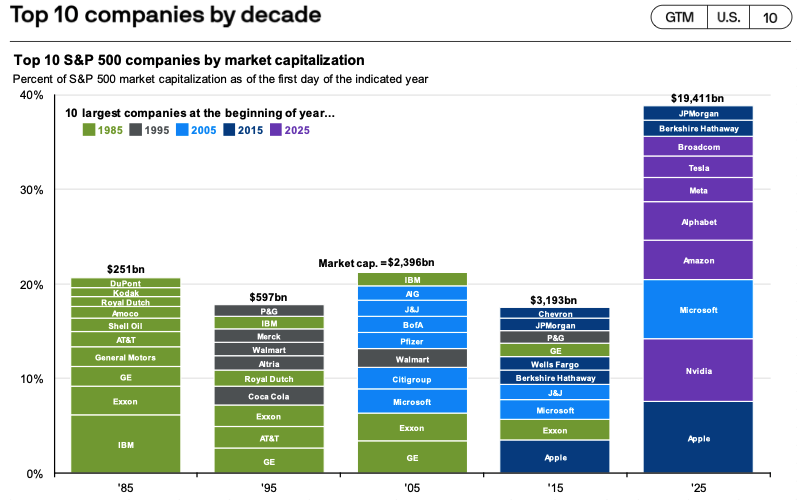

Source: JPMorgan

Diversify and Pay Less

Sort of doing nothing. Valuations look similarly now in the AI boom as they did back during the dotcom boom. If that worries you, you could hold a neutral position on tech/growth and allocate the rest of your stock portfolio to international developed markets.

It’s a bit cute, and you would want a professional to do it for you. However, if you exclude Silicon Valley, the US appears to be a more expensive version of Europe, but with less cash flow to investors. A cap-weighted US tech and internationally developed stock portfolio would theoretically resemble a less expensive version of the S&P 500 (Russell 1000). Please don’t do this without professional advice.

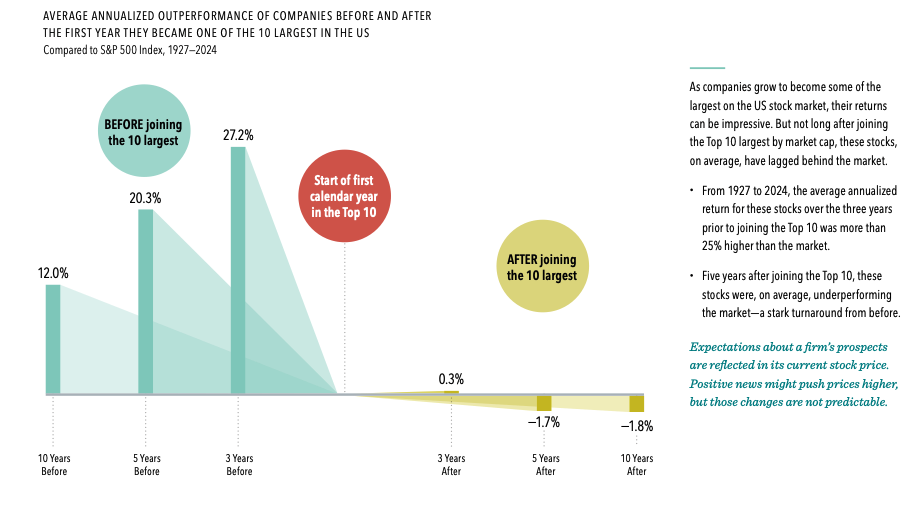

Big Get Bigger, Until They Don’t

Source: DFA

A losing concentrated position is a killer. We have extensive research that shows today’s winners tend to lag behind over the longer term. One year is bad enough, but underperformance over multiple years is brutal. So piling extra cash into the largest companies in the S&P 500 is kind of a losing proposition in the medium- and long-term.

Source: JPMorgan

While we don’t know what the future holds, history suggests it will look different. Today’s largest companies look different from those in the past. If there is anything certain, tomorrow’s winners will look very different from today’s.