The inflation numbers for August came in hotter than expected, rising 0.1% for the month against the falling forecast. On the surface, it does not seem too bad, considering inflation is over 8% for the year, and it paused in July. The Fed and investors were by far and away hoping that they had seen the peak and that inflation would begin to fall.

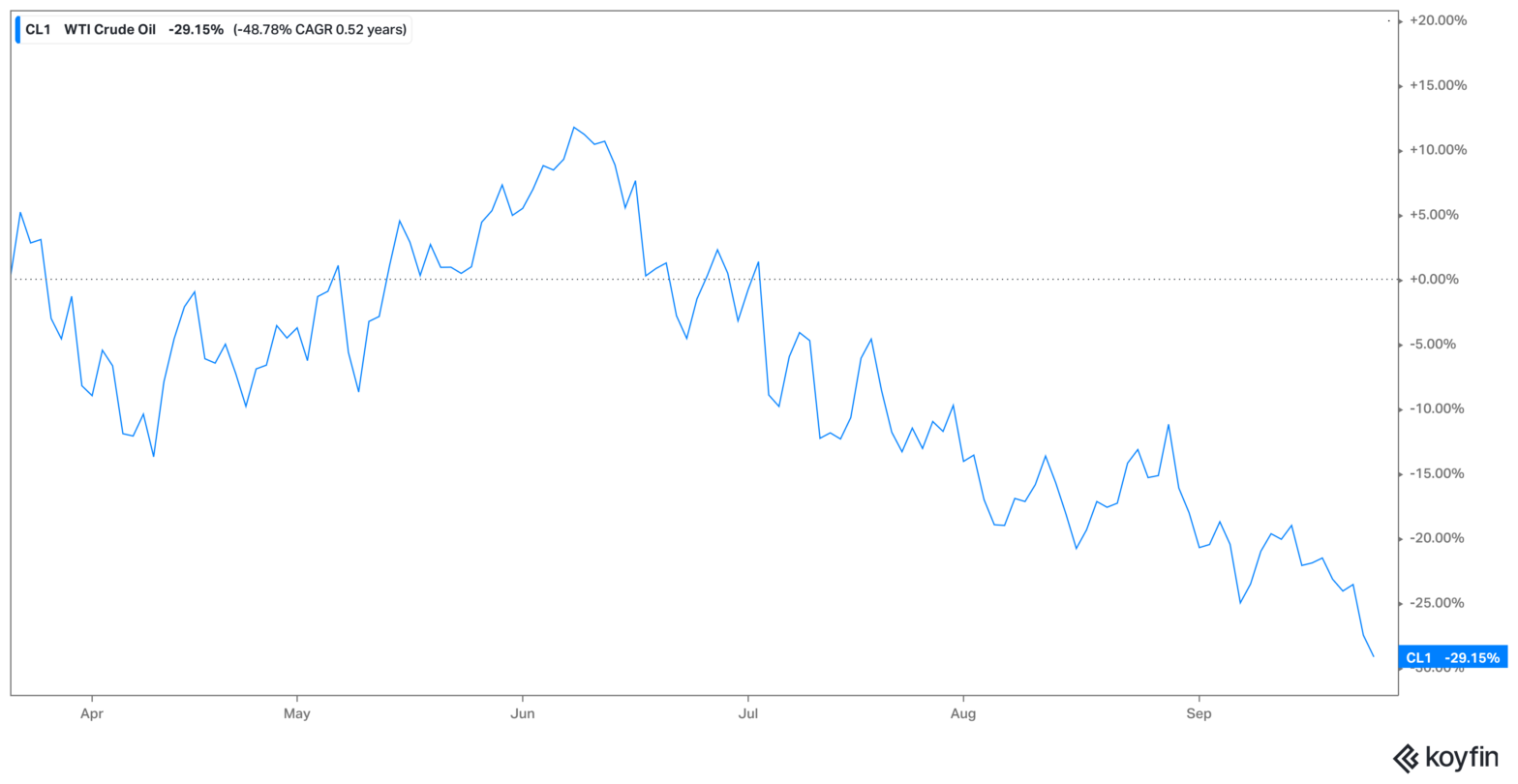

While disappointing to see the modest rise, the primary problem with the inflation report is the underlying components. Core inflation, which ignores food and energy for their volatility, rose by 0.6% in August, double July’s increase. The most significant reason inflation has stalled out the past two months is that gasoline prices have come down rapidly. Gasoline fell 7.7% in Jule and another 10.6% in August, stalling the headline inflation numbers.

Using the Strategic Petroleum Reserve

While consumers are thrilled to be paying less at the pump, observers are concerned that the reprieve in gasoline prices could be short-lived. In March, President Biden announced the release of oil from the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve to combat the supply shocks resulting from the war in Ukraine and the pandemic. The goal is to release approximately one million barrels daily for six months, ending in October. According to a Reuters article, the Biden administration is not expecting to begin another program:

“The Biden administration is less likely to release barrels from the SPR after October if benchmark oil futures continue to drop. Last week, the 50-day moving average of US and European prices both fell below the 200-day moving average, noted research analyst Paul Sankey said.”

Oil Backwardation

Let’s get into that financial market jargon a little because it has important policy implications beyond energy markets.

I have written about oil futures markets and oil before:

Oil markets are currently in what is called “backwardation.” There are two ways in which oil traders buy oil.

- Through the spot price, the cost of buying a barrel of oil now.

- Then, there is the futures price—the cost to purchase a barrel of oil sometime in the future.

With higher prices now and lower prices in the future, the classic textbook answer would say, “Hey, everybody thinks oil is going to fall in the near term.” But that is not necessarily the case in reality. Even faster-to-respond shale producers can take over a year for production to come online.

The most significant factor to consider for backwardation is OPEC. OPEC does not have the influence it once had, but it can ramp up production to drive down prices, hurting shale producers who need higher prices to profit. US producers are afraid to commit to too many drilling projects because OPEC can ramp up production and destroy their profitability. The threat of OPEC is why prices months from now are lower than the prices of today.

Refilling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve

The Biden administration uses the SPR release to ease US consumers’ pain at the pump. That oil is not being replaced with new oil production, bringing the SPR to its lowest since 1984. At some point, the US will have to replenish its reserves.

The Biden administration’s release of the SPR has affected gasoline’s recent plunge. More oil out there did drive down prices. There is also the less clear implicit effect that filling the SPR back up will have on the market price for oil.

If the Department of Energy said, “we need to fill the SPR back up ASAP,” it would likely drive up prices. Nobody wants that, especially politicians, during an election year.

One of the biggest reasons oil producers have been reluctant to increase production is that they got burned by producing too much oil only a few years ago. Investors lost hundreds of millions of dollars expanding production, essentially subsidizing American consumers.

To provide price stability, the administration will likely guarantee the purchase of oil at a predetermined price. They will fill the SPR back up, but the implications are much more comprehensive. In a sense, the government becoming a “purchaser of last resort” gives oil producers some certainty in how much they can safely produce.

The New Supply-Side Economics?

The Biden administration will likely support the purchase program but is still trying to determine the best price for taxpayers. But this policy could go beyond being a short-term solution and do a lot to fix the supply side issues the economy experiences after a collapse.

There are significant problems facing the economy as a result of ongoing supply issues. The Federal Reserve can do nothing to fix supply chains and reduce inflation. Continued supply constraints are a powerful driver of the persistent inflation we are seeing right now. Increasing interest rates will not get more oil out of the ground or build houses.

There are plenty of places where the free market falls short of delivering things Americans want. The boom and bust cycle has left one of the most resource-rich countries in a housing crisis, oil shock, and various other shortages.

The government can and should do more to take a more targeted approach to supply chain bottlenecks. In the world after the Global Financial Crisis, there was not enough investment for producing the things we consume. The deleveraging process was brutal for consumers and businesses, and the government did not do enough to fill in the holes where markets failed. Using targeted supply-side policy, such as guaranteeing oil purchases via the SPR, could be an excellent way to fix shortfalls in housing, childcare, and healthcare.