The price of oil is surging, and so is the debate over what is causing the fastest runup in recent memory. As we approach the midterm elections, candidates and the broader media will continue to discuss gas prices and inflation. What has caused the surge in oil prices, and can policymakers do anything about it?

The price of crude oil is volatile. Various factors influence its price: supply and demand, weather, geopolitical events, and more. There are two significant types of crude oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent North Sea Crude (Brent). The pricing mechanism for Brent determines roughly two-thirds of the world’s oil supply.

Over the last two years, the price of oil has been wild; WTI even traded negative in April 2020. However, to understand the surge we are experiencing right now, we must go back further than the pandemic.

2010s Oil Glut (Too Much!)

Believe it or not, “we” actually produced way too much oil in the previous decade. There were a variety of factors that led to this:

- Oversupply of North American shale

- Geopolitical rivalries among oil-producing nations

- Falling demand from Chinese economic deceleration

- Long-term shifts in fuel efficiency and green policies

OPEC lost some of its ability to maintain price stability as U.S. shale production increased rapidly and other supply lines came into play. The oil price was above $125 in 2012 and remained above $100 until late 2014. In late 2014, prices began to spiral down, hitting $30 in 2016.

In 2016, prices began to recover to the mid-$40 range, but producers and investors were nervous about investing more capital in building and expanding capacity. By 2018, prices had recovered to the 2015 levels, and shale production ramped up just as concerns of a global economic slowdown, leading to a one-month decline in oil prices of 22%.

How Could There Possibly Be Too Much Oil?

Wall Street. After the Global Financial Crisis, interest rates fell to nothing and stayed there for years. Low-interest rates fueled (intended) a boom in the shale fields. Investors needed to put capital to work and were looking to take on some risk.

Too much of a boom. Investors were plowing capital into loss-making projects expecting (hoping) for future profits. Too much speculation, and the aforementioned dynamics, set the stage for huge losses when oil prices plummeted. The expansion at any cost mantra became too costly. Analysts have estimated that investors lost over $500 billion chasing production growth. Now investors have found discipline and are focusing on returns on investment.

That Leads to Now

After the shale boom, glut, and subsequent bust, OPEC became more disciplined in practice. It has acknowledged that it doesn’t have the same influence in markets it once had, so it will be more disciplined when prices fluctuate. With more cautious shale investors and producers, consumers will be more reliant on OPEC producers that are much less price-sensitive to short-term fluctuations in price.

The Mechanics of Backwardation

Oil markets are currently in what is called “backwardation.” There are two ways in which oil traders buy oil.

- Through the spot price, which is the cost of buying a barrel of oil right here and now.

- Then, there is the futures price. The cost to purchase a barrel of oil sometime in the future.

Traditional economic theory would suggest that growth in overall demand as the global economy recovers would lead to higher oil prices. However, that is not what we are seeing right now. It is more expensive to buy a barrel of oil today than six months from now, and we call that “backwardation.”

It can take up to a year to bring shale rigs up and running again. After the bust in oil prices, capital investment for new wells fell off a cliff and stayed there. Even with surging oil prices, inventors are reluctant to pour more money into shale. Shale producers are worried about getting burned by falling prices again (backwardation). After years of low prices and subsequent underinvestment, there is not enough infrastructure to meet the current surge in demand, even if producers wanted to pump oil right now.

The other part of this equation is OPEC. OPEC may not have the same influence on prices as it once had, but it does maintain the threat of ramping up production to drive down oil prices, hurting the shorter life cycle of shale well producers. Shale wells are cheaper to build but have a shorter life expectancy than traditional wells. Because there is always a threat of more supply coming online from OPEC production, shale investors will be more reluctant to produce in the face of higher prices.

Is It President Biden’s fault?

No. Presidents have much less influence on the economy and markets than they are given credit for, but that won’t stop them from taking credit or receiving blame. Sure, some policies can influence the margin over the long run, but that is not what we see here. The policy shifts to green energy or fiscal mismanagement are far from the causes we are witnessing today.

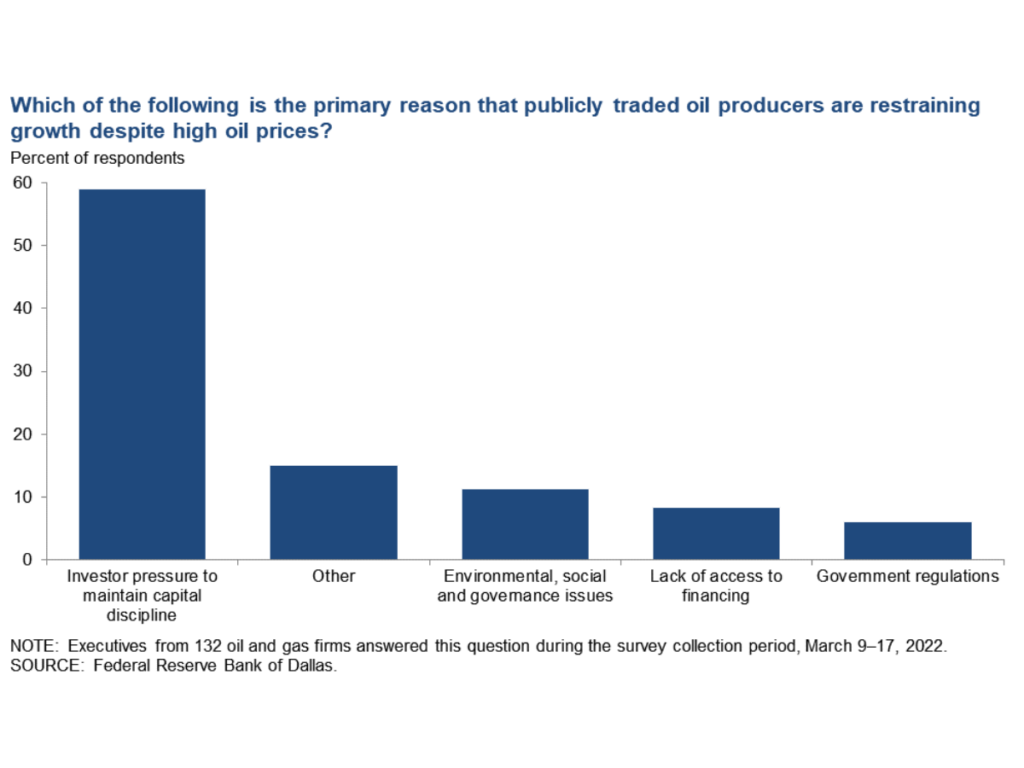

In the oil survey conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, the number one reason oil executives cited for not drilling is “capital discipline.”

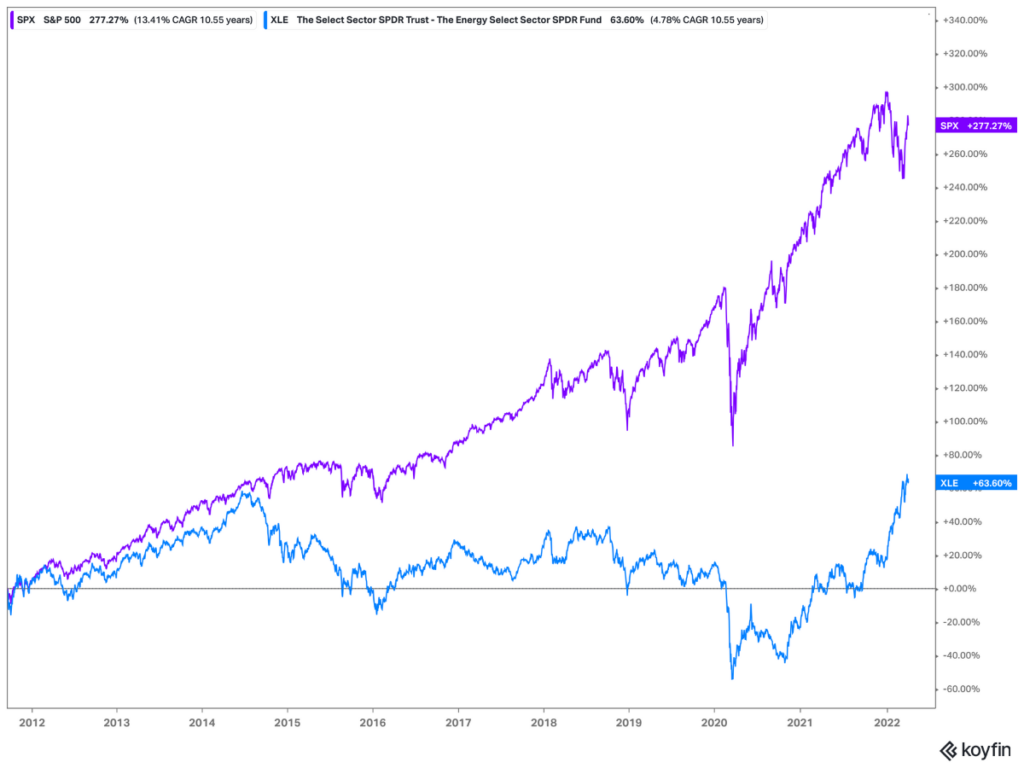

Wall Street wants to make money on its investments. Oil executives will be sitting on profits and returning capital to investors for the time being. Investors lost a lot of money in the past seven years and want to get it back. The graph below shows that the energy sector has significantly lagged behind the S&P 500 Index. It has been a challenging few years for oil executives to face investors.

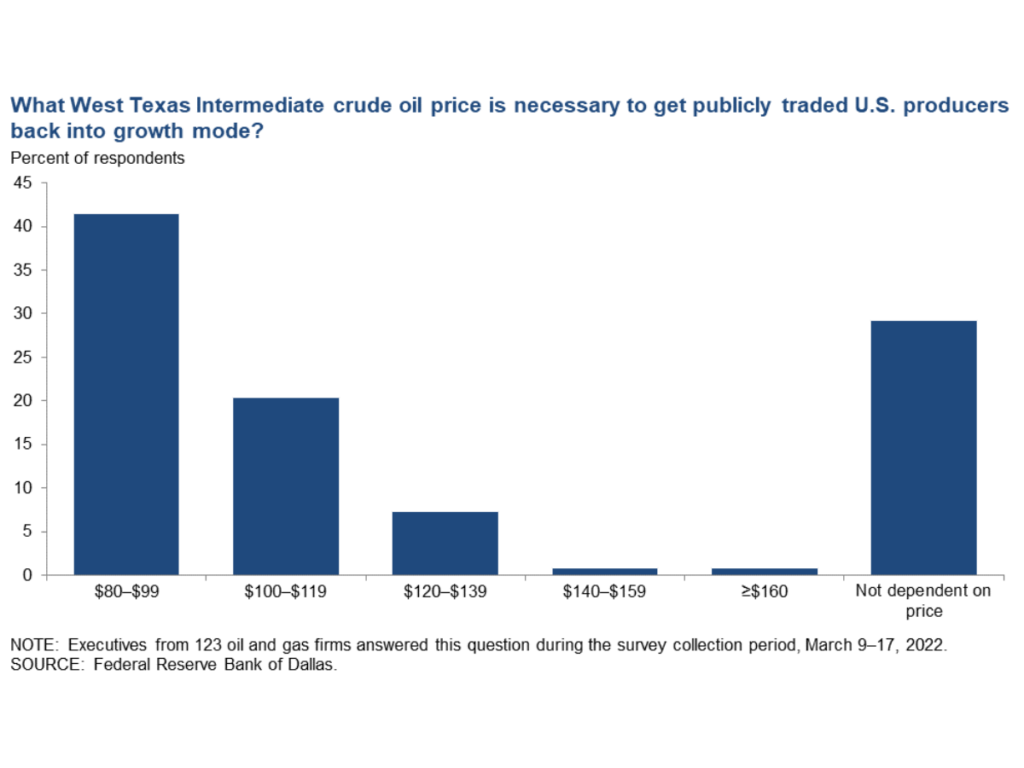

Perhaps the most shocking thing in that survey from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas is that about 30% of respondents said they would not reenter growth mode no matter the oil price.

The current administration is releasing barrels from the strategic reserve, likely in conjunction with other nations, in an extensive attempt to relieve gas prices. However, releases have had very mixed results on prices in the past. Releasing oil from reserves is not production. Running down reserves is typically a bullish signal for oil prices. We need more oil production to get prices to fall.

A Lot of It Is Still Supply Constraints

At the pandemic’s beginning, global energy demand plummeted—all energy, not just oil. Coal and oil production ground to a halt and could not be turned back on with the flip of the switch. Shutting down coal in China increased the demand for oil. The wind stopped blowing in the North Sea, increasing the demand for oil and gas. Russian oil and gas disappeared from the global market. Shale investors don’t want to get burned again. All of these things have led to the current tightness in oil.

Ultimately, there needs to be more oil production for oil prices to come down. Unfortunately, nobody has a “more oil” lever to pull in the U.S., so we are at the mercy of the willingness of oil companies to produce. If oil executives and investors believe that oil prices will fall over the next two years, they will hesitate to invest in new production. One of the oldest axioms in commodities is that “high prices are the cure for high prices,” so the longer prices remain elevated, the more likely we are to see higher production and then falling prices.