So, how are things going in the economy? Not great. But not terrible either. While the jobs market remains strong, the biggest concern for consumers and policymakers is inflation. The Fed is rapidly increasing rates to tame inflation.

However, the Fed may not be able to do a lot to cure the supply chain issues currently driving inflation. Increasing interest rates won’t create refining capacity or make chip manufacturing easier. However, rate increases will bring down the rosiest of forecasts from businesses, and they will scale back investment and hiring.

Reigning in future expectations about growth could bring down inflation. The problem is that it is an inexact science, and the Fed could go too far and cause significant economic pain via higher unemployment.

Inflation Is the Only Thing That Matters

Higher prices are definitely weighing on consumers, as consumer sentiment has hit the lowest levels since 2009, suggesting consumers expect things to not look so great over the immediate future. There is evidence that consumers are already cutting back as inflation eats into their budgets.

Worryingly, Americans are googling “recession” the most since 2004. While we have not yet technically entered a recession, many people think one may be on the horizon. So, what is a recession even?

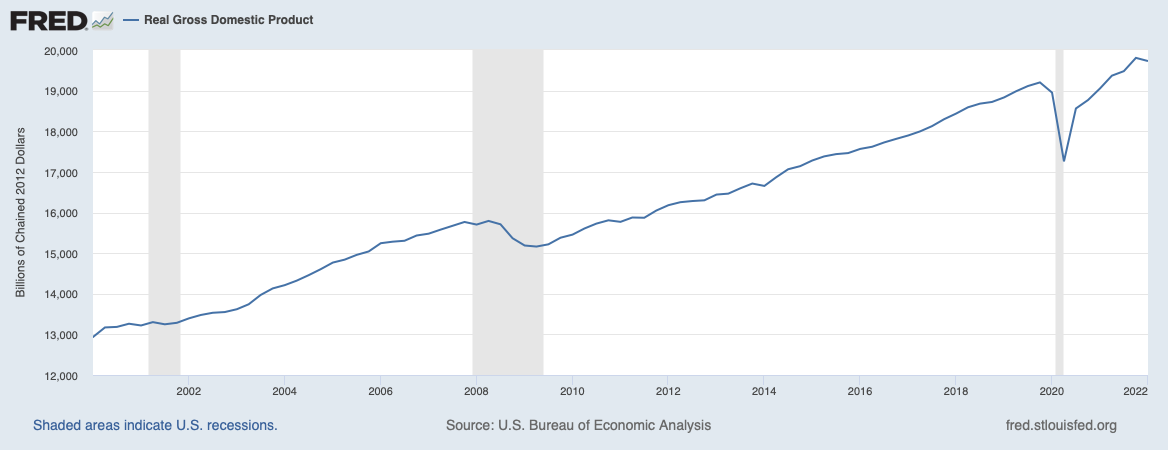

Two Quarters of Declining GDP?

The most common “textbook” definition of a recession is two consecutive quarters of negative real (inflation-adjusted) GDP. It is the most likely response you will hear from that one guy in your office. It is the definition most cited by people who took an econ class one time 100 years ago and then never cared to read up on the subject ever again. Economists consider that definition insufficient, at least for defining one in the US.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the official scorekeeper of the US economic business cycle, uses a variety of factors from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank’s FRED database to determine if we are in a recession or not:

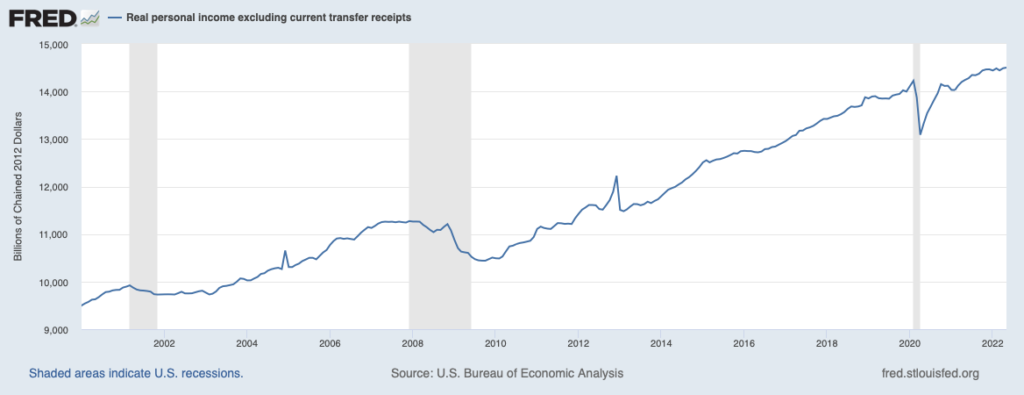

- Real personal income less transfers (PILT)

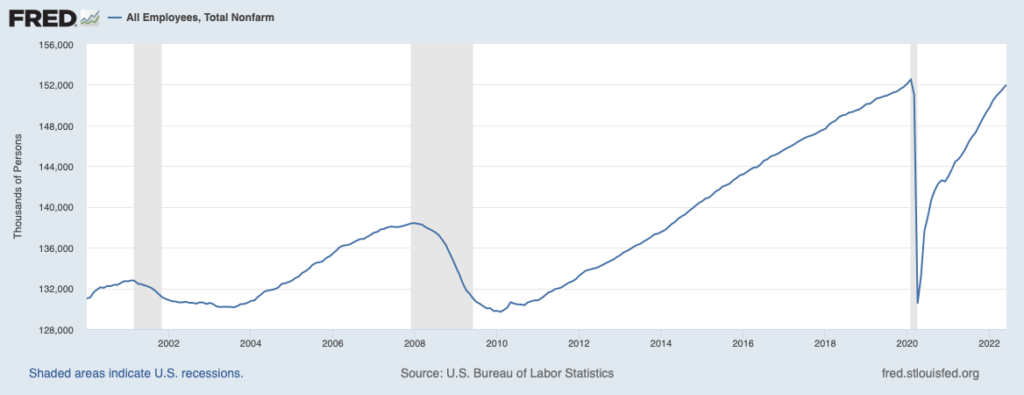

- Nonfarm payroll employment

- Real personal consumption expenditures

- Wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes

- Employment as measured by the household survey

- And industrial production

The NBER does not have a static method or weighting in which it applies these factors to determine a recession. Each recession is a little different in severity and which factors cause the most pain. However, the NBER has put the most emphasis on real personal incomes and nonfarm payrolls in recent decades.

One factor can be thrown way off in one period but still be primarily offset by the other factors in that period, meaning no recession. A recession is a broad-based and sustained contraction of economic activity, not just one or two bad numbers that make the CEO of a car company masquerading as a transformative tech company feel bad.

Part of the reason the NBER uses a different methodology from the “two quarters” definition is that GDP data can be pretty slow in coming out, and then the numbers are subject to revision. Using broad-based monthly data allows for more precise reporting of economic peaks and troughs. Also, the economy can enter and exit a recession within two consecutive quarters.

From the NBER:

The NBER’s traditional definition of a recession is that it is a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months. The committee’s view is that while each of the three criteria—depth, diffusion, and duration—needs to be met individually to some degree, extreme conditions revealed by one criterion may partially offset weaker indications from another. For example, in the case of the February 2020 peak in economic activity, we concluded that the drop in activity had been so great and so widely diffused throughout the economy that the downturn should be classified as a recession even if it proved to be quite brief. The committee subsequently determined that the trough occurred two months after the peak, in April 2020. An expansion is a period when the economy is not in a recession. Expansion is the normal state of the economy; most recessions are brief. However, the time that it takes for the economy to return to its previous peak level of activity may be quite extended.”

It is also critical to note that it can take a long time to declare a recession and its end. We can be well on our way into an economic expansion before the NBER says a recession happened.

Our determination of the trough date in April 2020 occurred 15 months after that date, in July 2021. Earlier determinations took between 4 and 21 months. There is no fixed timing rule. We wait long enough so that the existence of a peak or trough is not in doubt, and until we can assign an accurate peak or trough date.”

If GDP falls by only a little for two quarters but other factors remain stable, it is feasible that the NBER may not declare a recession. They use a basket of factors beyond GDP to determine the breadth, depth, and length of economic declines when declaring a recession.

Most recessions do include two-quarters of falling GDP. However, this current economy is one of the weirdest anyone has ever seen. We may see two-quarters of falling GDP (real GDP) while employment remains quite strong.

Are We in a Recession Right Now?

The two factors the NBER has watched most closely in determining a recession over the past several decades, personal income and employment, have been relatively steady, if not robust. Obviously, real personal incomes are struggling as inflation eats away the value of a paycheck, but people are still earning and spending.

There has been a lot of press about the crash in the tech sector as valuations come back to earth and layoffs begin at some large tech firms, but the economy as a whole is adding jobs. Nonfarm payrolls remain pretty strong and are showing no signs of weakening. One sector’s struggle has not broadly affected the overall job market or economy.

Economists Are Bad at Predicting Recessions

Economists and business leaders are notoriously bad at predicting recessions. Nobel prize winner Paul Samuelson famously quipped, “The stock market has predicted nine out of the last five recessions.” An IMF (International Monetary Fund) paper found that of the 153 recessions in 63 economies between 1992 and 2014, economists correctly predicted only five recessions in the year preceding the recession.

That is not to say economists are dumb or bad at their jobs, but predicting the future is impossible. It is impossible to predict the timing and severity of economic shocks (that is literally why it is called a shock) and the effect of any policy response. Economists thought inflation would have fallen by now, but that was before the resurgence of COVID (especially internationally) and the war in Ukraine.

Big exogenous shocks commonly throw off forecasts. Around 2018-2019, many predicted an economic downturn as tariffs began to weigh on global trade, affecting consumers. And we all know what ended up happening in early 2020, and nobody predicted the pandemic collapse. The rapid economic recovery was even harder to predict.

If we are in a recession may not even really matter this time. The Fed is far more concerned about inflation at the moment, so it will continue its rate hikes and quantitative tightening even if economic growth stumbles. Politicians will also have difficulty responding with fiscal stimulus as the midterms approach. Nobody is coming to the rescue should the economy slip into recession, but with solid employment numbers, a rescue may not be necessary.