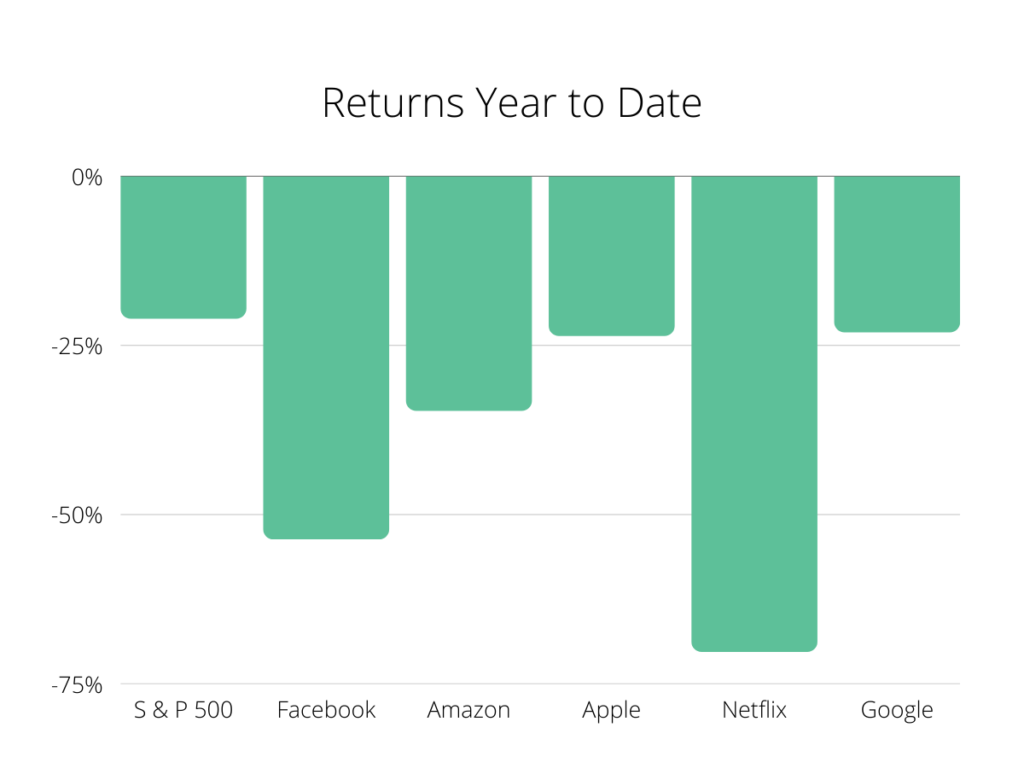

Markets have been getting a lot of attention lately beyond the financial media. The S&P 500 is down 21%, the tech-heavy NASDAQ 100 is off over 29%, and the smaller company-oriented Russell 2000 is down over 24% year to date.

Investors have a lot of concerns over the economy right now:

- Inflation (the author still thinks it’s transitory)

- The Fed is increasing rates rapidly

- Looming recession? (although likely not a severe one)

- Gas prices are constraining consumers

- What will happen to the housing market?

- Businesses are cutting back.

- Hiring freezes and layoffs

- Continued supply issues

- Supply chain issues that aren’t going away

- China lockdown

- War in Ukraine

- Perpetual underinvestment post-Global Financial Crisis

Investors are facing a lot of headwinds and negative headlines as the Fed and policymakers all but guarantee the fun is over. If a recession does occur, the Fed isn’t likely to cut rates to bail out businesses and the economy, and Congress lacks the political capacity to come to the rescue. How did we get to this point? It all started in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis.

The Lackluster Recovery

The policy response from Congress in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) was so lackluster that the recovery took forever. The result was missing aggregate demand from consumers. In a world with anemic economic growth, it seemed tech shares were the only place investors could go for reliable returns. That trend was amplified during the pandemic and subsequent economic stimulus, effectively extending that tech-oriented cycle.

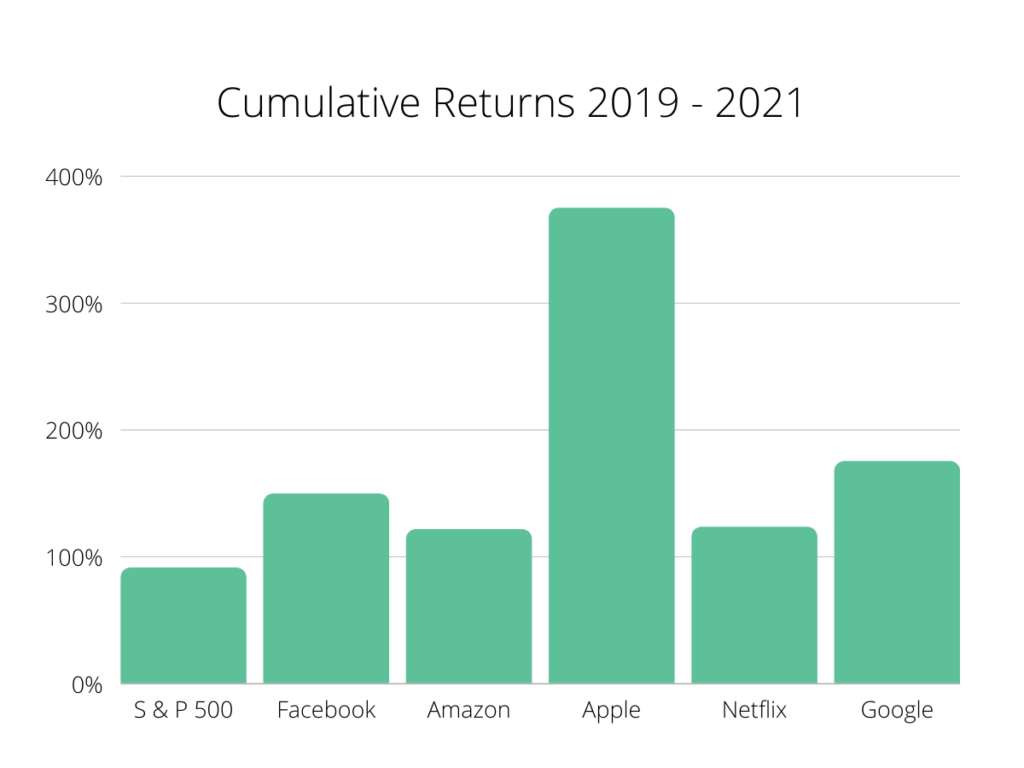

The world after the GFC was all about cost-cutting and shedding debt. Firms invested heavily in software and the cloud to keep expenses low, so big-tech companies fared quite well. The alphabet soup of FAANG became the buzz of the investment world, carrying indexes to record high after record high.

Without fiscal policy, the rebound from the GFC was lethargic. The weak policy response from Congress led to slow and uneven economic growth. The Fed set interest rates low to stimulate the economy. Firms decided to borrow at ultra-low rates and buy shares–essentially refinancing.

Now that interest rates are increasing, tech stocks are in a steep decline, leading the market to lower. Hopefully, the current market turmoil and policy shifts will lead to more productive capital deployments over the next decade.

Cost Cutting Leads to Poor Investment

The problem with this prudent approach to capital investment is that it led to chronic underinvestment in the part of our economy that produces things. We keep hearing about supply and supply chain issues because firms under-invested, running lean operations after the GFC.

People sat idle or underutilized for years. People were underemployed. Sure, jobs might have technically recovered, but remember that someone with a degree working part-time outside their field is technically employed. Underemployment leads to stagnation, where consumers have less spending power, leading to fewer growth opportunities for firms. It was always a problem of missing demand.

Even before the GFC, globalization pressured profit margins and led to cost-cutting and lean supply lines. Firms did not build any resiliency into supply chains; it was all by the seat of the pants in the name of profit margins.

When firms have fewer growth opportunities, management will focus on cost-cutting to grow profits instead of capital investment. It is a big deal because capital investment is a precursor to well-paying job growth. If firms don’t have growth prospects and face low interest rates, they will use bonds (issue debt) to purchase stock. It’s a simple but effective trick to support share prices when growth prospects are relatively weak.

A poor policy response from Congress after the GFC ultimately led to underinvestment in the economy. The Fed was the “only game in town” and used the Fed Funds Rate and Quantitative Easing to signal favorable monetary policy over the foreseeable future. An easy money policy and the explicit purchase of bonds signal investors to take on more financial risk in the form of equities.

Pulling vs. Pushing a String

The Fed can easily cause an economic downturn by increasing rates, but stimulating the real economy is more difficult for it to do. The Fed’s tools have more of an effect on financial assets during a downturn. They can cut rates and increase asset prices, but that does not necessarily mean more investment and jobs. Only Congress can implement the policy directly affecting the real economy by allocating dollars and resources. The result is a pre-pandemic-decade of financial asset growth while the real economy lagged.

The more speculative and reliable revenue growth (revenue does not mean profits) oriented stocks did quite well in this environment. The more attached to the old economy a firm’s operations, the less its stock participated in the bull run. It becomes challenging for a CEO to justify capital investments when their stock price has lagged for a decade and the economy as a whole isn’t growing.

Why It All Matters

Where am I going with all of this? Well, things seem to be shifting a bit in the other direction. Yes, the historic sell-off in tech stocks is a bit of a natural correction. Part of that run-up has resulted from too much money flowing into tech in an otherwise low-economic-growth world.

However, supply chains have broken down due to lean inventory practices and underinvestment in the old economy. The actual economy needs oil products, consumer goods, trucking, and housing–all in high demand, and we have not significantly invested in the economy’s capacity to supply these things.

Walmart and Target recently announced that they have too much inventory. This problem is partially from management misreading the shift in consumer demand. Consumers are shifting away from home goods as things return to normal(ish). Misreading the transition is only a tiny part of the inventory problem.

There is also a longer trend in play that will significantly impact the economy. The realization that the failure of just-in-time inventory management led to zero resiliency to supply shocks. CEOs will now look to hold more inventories as insurance against supply shocks. There is a movement to re-shore or near-shore production and supply lines, removing some of the risk to supply chains.

The just-in-time inventory management acted to smooth out the business cycle. Managers used computers and advanced tech to produce what they needed when they needed it, keeping inventory light and predictable. The “new” inventory practice will shift to “just in case.” Keeping higher inventories will be harder to maintain and predict for managers. This difficulty will reintroduce the ebb and flow of the unpredictable business cycle to the economy. This change will affect how investors think about this next decade compared to the last.

What Comes Next?

The movement to reinvest in the real economy and build resiliency into the supply chain will require a lot of capital investment, which will support higher worker wages. It will be more expensive but more resilient, equitable, and sustained overall. The whiplash we are experiencing from services to goods and back will have lasting effects on how businesses invest. That long-term change in investment is ultimately good for workers and consumers but will likely cause more volatility in the business cycle. However, what is good for the consumer is good for the economy, as consumption is around 70% of the US economy.

The stock market and economy will look much different over the coming decade, and that will be good for workers and investors. Economic and business investment shifts will affect domestic and international stock markets. While investors are currently flocking to cash flow safety, they will be hesitant to flood back into tech stocks with no proven business model or path to profitability (Uber and meal delivery). Investors will seek supply chain management, infrastructure, and manufacturing businesses.